It was clear to the victorious Allies of World War II well before the German army capitulated in 1945 that the entirety of German society would need to be cleansed of Nazi influences and effects, and that the Germans would need to be “re-educated” in democratic values. It was relatively simple to repeal Nazi laws, remove symbols of the National Socialist regime from the public realm, cull unwanted books from the libraries, obliterate the swastikas on forms and paperwork, and change street names. A much greater problem was what to do with the some 8.5 million members of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), and the many more millions out of a German population of 70 million who had belonged to one or another Nazi organization – how to denazify them.

While legal proceedings such as the 1945/46 Nuremberg Trial of the major war criminals were judicial prosecutions of specific crimes, denazification took a different shape. Its goal was to politically cleanse German society and make sure that people who had been involved with the Nazi regime were excluded from important positions in society and the future state institutions.

Internment and denazification procedures

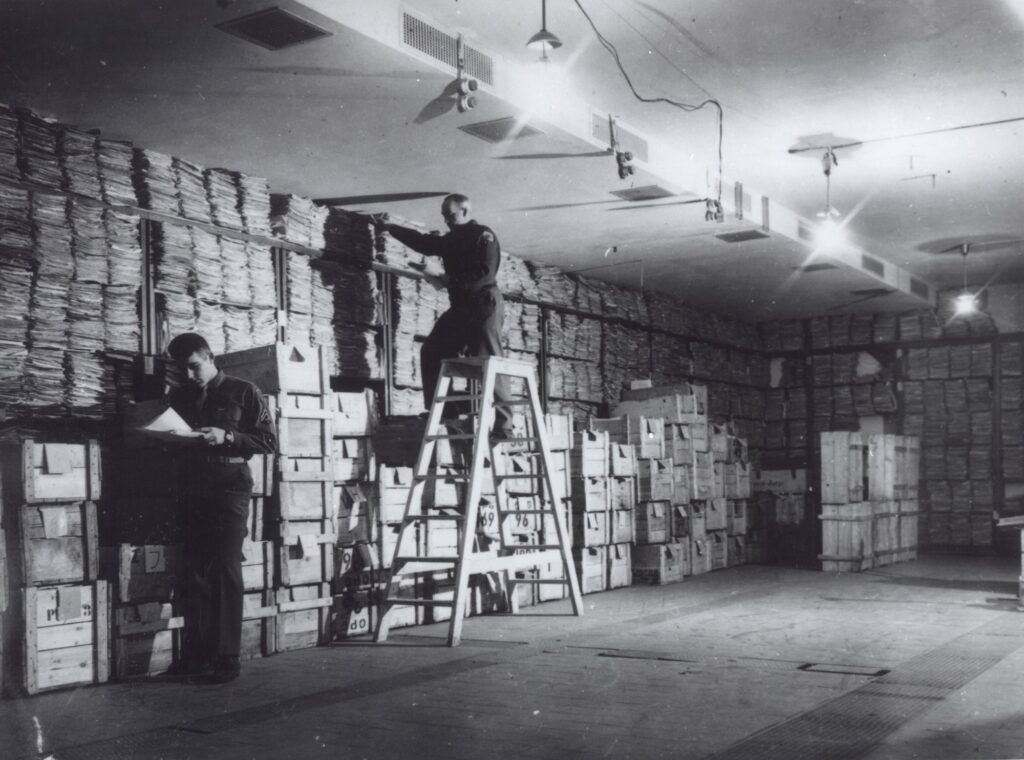

Immediately following the end of the war, active Nazis and functionaries – in particular, police, members of the SS, and civil servants – were removed from their posts by the Allies and subject to “automatic arrest.” Between 1945 and 1950, the Allies preemptively detained more than 400,000 Germans in internment camps without case-by-case reviews. In the Soviet occupation zone, it was not only former Nazis, but also many people the Soviets considered political opponents, who were detained in what were called special camps.

There was disagreement among the four occupying powers about the specifics of how the political cleansing should be carried out; initially, there was neither a joint course of action nor a joint objective, and the denazification procedures differed accordingly. It was not until January 1946, after long discussion, that the Allied Control Council issued Directive no. 24 containing guidelines for a coordinated approach across Germany.

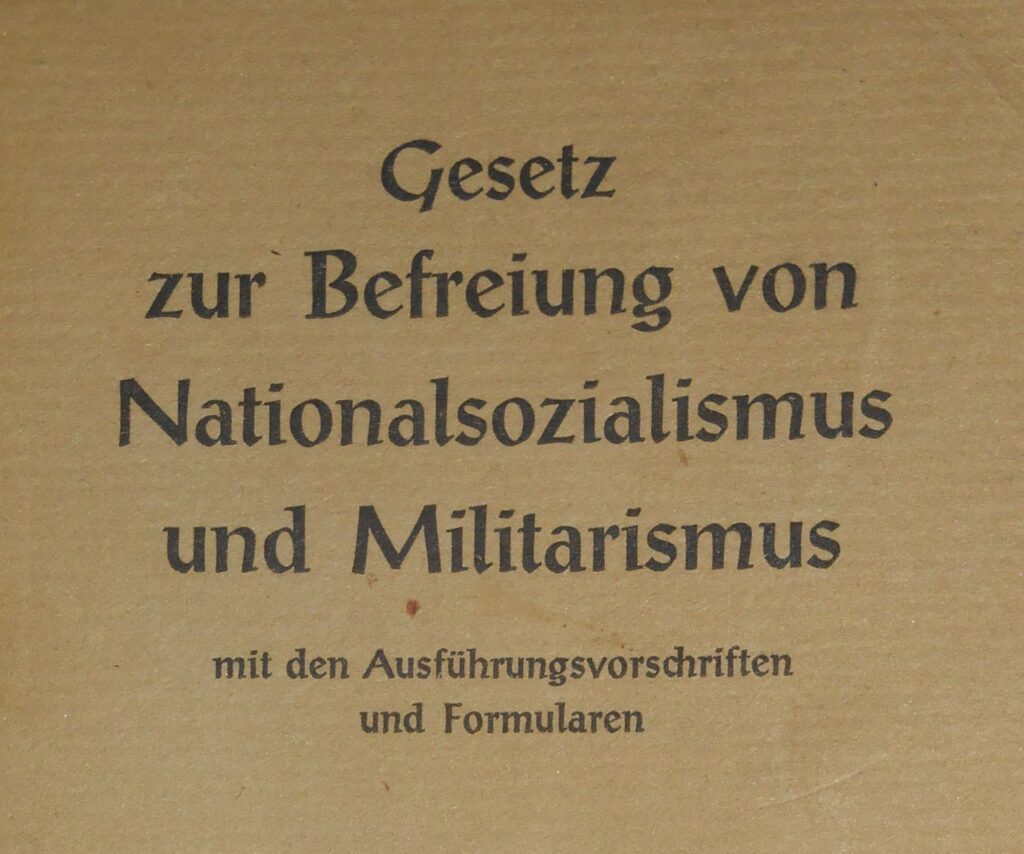

German “Law 104 for Liberation from National Socialism and Militarism” of March 5, 1946 established five categories for classifying people. They were: “1. Major Offenders, 2. Offenders (activists, militarists, and beneficiaries), 3. Lesser Offenders (probation group), 4. Followers, and 5. Persons Exonerated.”

The occupying powers turned responsibility for denazification over to the Germans as early as 1945/46. In each occupation zone, various forms of commissions, committees, and denazification tribunals called spruchkammer, made up of former resistance fighters, unionists, professional and lay judges, and similar people, vetted individuals. In quadripartite Berlin, there was a joint procedure for the four powers – at least on paper. In all of the occupation zones and/or sectors, the classification and ruling by the spruchkammer, commissions, and committees was made on the basis of a comprehensive questionnaire. The respondents had to provide detailed and truthful information about their political biography, including membership in the Nazi Party or any other Nazi organization. The sanctions that might be imposed included fines, forced retirement, or even confinement to a labor camp. Many people produced exculpatory sworn statements. Since incriminating documents were often difficult to unearth, those written attestations – from friends or neighbors, say – contributed significantly to the fact that the overwhelming majority of cases were classified in the 4th category “Followers.” Only 1.4 percent of the people undergoing denazification ended up classified as “Major Offenders” or “Offenders.” An official ruling that a person had been classified as “Exonerated” or a “Follower” – and by association, the exculpatory sworn statements – were later to be known colloquially as “persil” certificates, a reference to a popular laundry detergent, meaning the document had “whitewashed” the possible guilt of its holder.

Differences between the four occupation zones

Although the Allies had all agreed on the five categories of culpability, the denazification process continued to be implemented to differing degrees in the individual occupation zones. The Americans carried out the most extensive bureaucratic operation.

They not only fired people who had held key positions during the Nazi regime, but also anyone who had been an “active” Nazi. But that rigorous and constantly expanding political cleansing soon caused a shortage of administrative manpower; the procedures dragged on; the unsystematic actions, which the subjects of denazification perceived as arbitrary, undermined the American’s stated aim of democratization.

Denazification in the British and French occupation zones was much smaller in scope than in the American zone and was handled in a far more pragmatic manner. The British prioritized the efficiency of the German administrative authorities, as well as the economy – taking into consideration the country’s level of destruction, along with housing and drastic food shortages – above any extensive cleansing of the ranks. Sometimes-contradictory guidelines were often implemented with long delays and the procedure was complicated. In the French occupation zone, denazification policies had a largely improvisational character, as well as being directed towards French national interests. The French focused their denazification on the civil service and large-scale industry; they made no effort to implement the kind of rigid political cleansing that was initially attempted in the U.S. occupation zone.

Denazification efforts in the Soviet occupation zone were much more resolute and had longer-term effects than in the three Western zones. In the initial months, the process was unsystematic, carried out by commissions and committees that sprang up spontaneously. The Soviets (as in the French occupation zone) then turned denazification over to the Germans as early as 1945. At the same time, denazification – alongside land reform and nationalization – functioned as an instrument to push through communist claims to power as part of the “anti-fascist, democratic revolution.” By contrast with the western zones, where the occupation authorities installed new personnel from across the entire spectrum of democratic parties, in the Soviet occupation zone, key positions in society and politics were often filled by comrades from the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), later to become the Socialist Unity Party (SED), the ruling organ of East Germany.

The situation in Berlin was different. Shortly before the western Allies marched into Berlin in early July 1945, the Soviet military administration for the whole of Berlin decreed that all former Nazi Party members be dismissed from the civil service. From then on, anyone who wanted a position of responsibility, with the authority to direct employees, had to first successfully undergo a denazification procedure ordered by the Allied Kommandatura, made up of the four occupying powers. Although there were differing priorities in Berlin, just as in the occupation zones, cooperation among the four victorious powers was shaped by pragmatism.

The end of denazification

With the procedures dragging on and the increasingly strained relations between the Western powers and the Soviet Union that would culminate in the Cold War, any interest in comprehensive and thorough denazification waned. More than before, the aim became to win over Germans to the new order to be established in East and West, respectively, instead of pushing them away. Although the majority of Germans initially embraced denazification, by 1946, more and more rejected it and it became a campaign issue that the newly formed political parties used to appeal to the millions of former “simple” or “nominal” members of the Nazi Party. The Soviet zone strategy, begun in early 1946, of integrating large segments of a population that had been incriminated in Nazi activities, at least on paper, haunted the KPD and then the SED, which soon became known colloquially as the “great friend of small Nazis.” In the western occupation zones, too, the “small Nazis” were treated with increasing leniency, accelerating the end of denazification. The spruchkammer became what one study dubbed mitläuferfabrik or Follower factories that summarily placed possible Offenders in the lower category; expedited procedures were introduced, and the frequency with which the Allies passed amnesty laws picked up considerably.

In February 1948, the Soviet military administration announced that denazification in the Soviet occupation zone would cease within two weeks, by March 10. The western occupying forces followed suit. They transferred the authority for the process to the German state assemblies or parliaments. However, the official end of denazification in the West did not come until after the Federal Republic of Germany had been founded. On May 11, 1951, all parties represented in the German parliament, the Bundestag, including the KPD, passed “Law 131” with just two abstentions. It permitted any government employee fired in 1945 who had been categorized as a “Lesser Offender” or “Follower” to return to civil service. The following year in East Germany, parliament (the People’s Chamber) removed the last restrictions on former members of the Nazi party and armed forces (wehrmacht) – they could then once again take up jobs in sensitive areas of the inner government circle and the judiciary. The key difference between the regulations in West and East was that the West German rules acknowledged that former civil servants who had been in one of the lesser Nazi categories were entitled to reinstatement in their jobs, while in East Germany, they were deemed professionally rehabilitated, but state authorities were not required to hire them.

So had denazification failed? A look at the bottom line is certainly sobering. The number of people brought to account for active support of the Nazi regime was extremely small. Contrary to Allied hopes, it was impossible to uniformly dispense with the old elite during re-construction of the country, meaning that after 1950, offices in industry and government were often staffed by the same people who had worked there prior to 1945. Many people in the arts and academia also benefited from the dwindling impetus towards denazification. The authorities in both East and West early on came to the conclusion that the price of establishing a stable, post-war order was the liberal integration of former Nazi Party supporters, some carrying a lot, and some just a little baggage. The only sector in which denazification achieved any enduring effect was politics. Political parties that disseminated Nazi ideas found no long-term base in either of the two German post-war societies.