The train militaire français de Berlin (French military train) car that now stands on the Allied Museum grounds began its final journey on the evening of August 26, 1994. Not, however, on the rails, but on the bed of a heavyweight vehicle. It traveled from the Gare française in Tegel in the former French Sector along the city highway and Avus to the new Museum, which was just being built. Since then, it has recalled a little-known chapter in the Cold War, the Western powers’ military trains.

A Cold War Early Warning System

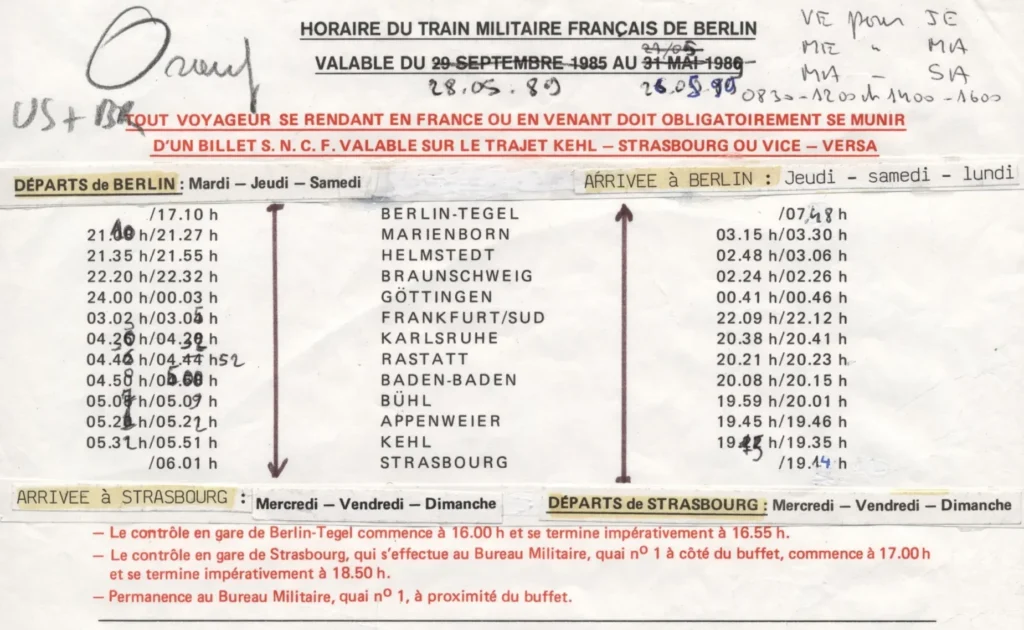

On September 10, 1945, the four victorious powers on the Allied Control Council agreed that the Western powers would be permitted to run a maximum of sixteen military trains ( or Duty Train, as the US Army called it) a day between Berlin and the Western occupation zones. These trains transported goods and passengers. For nearly five decades, they traveled the Potsdam – Marienborn – Helmstedt route across the Soviet occupation zone, later the GDR. On these ca. 200 kilometers, the Allied trains were pulled not by their own locomotives, but by ones belonging to the GDR state railroad, the Deutsche Reichsbahn.

The highpoint of every journey was the stop in Marienborn, where a border control took place on both the outbound and inbound journeys. The Soviet military checked the travel orders presented by the train’s Allied commander and compared them with the passenger lists. This took place outside the trains, which Soviet personnel were not permitted to enter. Passengers included members of the armed forces stationed in West Berlin as well as their friends and families. Germans were only allowed to use the trains during the first two years of their existence. Since 1961 at the latest, the doors of the cars were secured with special locks from the inside to prevent refugees from the GDR from entering them.

Despite the agreements of September 1945, increasing political tensions between the Western powers and the Soviet Union also impeded free travel to and from Berlin—until the Soviet blockade of Berlin brought the Western Allies’ rail transport to a complete stop on June 24, 1948. All the advance warning notwithstanding, the blockade caught the Western powers off guard, and they decided they had to be better prepared in future.

After the blockade was lifted and transport to and from Berlin resumed in May 1949, the Allies assigned their military trains the role of a sort of early warning system: By traveling daily through the Soviet sector, they could tell from the conduct of border checks or obstacles along the route whether new political complications were looming. Even the tiniest incidents were radioed in to the headquarters of the Western powers. Furthermore, by deploying the military trains, the Western powers insured the repeated integration of the Soviet Union into quadripartite responsibility for Berlin and Germany. The passengers on the military trains were probably barely aware of how politically explosive their journey was.